The Written Description Requirement in the United States

The “written description” prong of 35 USC §112(a) requires that the written description be sufficient to demonstrate that the inventor had possession of the invention being claimed at the time the patent application was filed. In a recent case from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, the Court found the written description requirement was not met by a provisional application to which the patents in suit claimed priority. The claims in suit were thus not entitled to the benefit of the parent application filing date, and were invalid in view of intervening prior art. This case is a useful reminder of the importance of the written description requirement and the potential dangers of relying on provisional disclosures when adding broadened claims in later applications.

D Three Enterprises sued SunModo Corporation and Rillito River Solar LLC for infringement of various claims of three patents. All three patents claimed priority to an earlier provisional application. The provisional application included 43 figures and 12 pages of descriptive text. The patents relate generally to assemblies for mounting objects such as solar panels on a roof while sealing the mounting location against water. Due to the timing of when the products entered the market, D Three needed to claim priority to the February 5, 2009, filing date of the provisional application for the claims issuing from its later non-provisional applications to be valid.

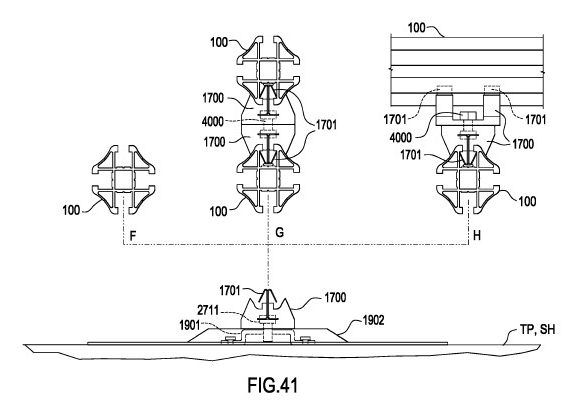

The provisional application disclosed various embodiments. All of those embodiments except the embodiment of Fig. 41 and related Figs. 27-33 included a washer. The only disclosure of a “washerless” assembly required a W-pronged attachment bracket 1700. The asserted claims were to a washerless assembly (or to an assembly with a washer but without specifying its location) but without limitation to the W-pronged attachment bracket. Hence, the issue before the court was whether the written description of the provisional application, and in particular Fig. 41, was sufficient to support these broader claims.

At the trial court level, The U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado found, on summary judgment, that the asserted claims were broader than the disclosure of the provisional application, and thus were invalid over intervening prior art. On appeal, the Federal Circuit agreed.[1]

To be entitled to claim priority to an earlier filing date, the written description “must clearly allow [a person having ordinary skill in the art] to recognize that the inventor invented what is claimed,” such that “the disclosure of the application relied upon reasonably conveys to [a person having ordinary skill in the art] that the inventor had possession of the claimed subject matter as of the filing date.” Ariad Pharm., Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc). The Federal Circuit, which for purposes of review of summary judgment drew all reasonable inferences in favor of D Three, agreed the embodiment of Fig. 41 (and related Figs. 27-33) disclosed a washerless assembly. The Federal Circuit also agreed that all but two of the claims in suit did not recite a washer and also were not limited to the W-pronged bracket. Thus, the Court explained,

Having determined that the 2009 Application discloses a washerless assembly, we must determine whether a PHOSITA would recognize “upon reading the [Provisional Application]” that any attachment brackets as claimed in the Washerless Claims could be used in washerless assemblies. In re Owens, 710 F.3d 1362, 1368 (Fed. Cir. 2013). We agree with the District Court that washerless assemblies using attachments other than attachment bracket 1700, which has “W[-]shaped prongs,” J.A. 2223, are not adequately disclosed, because the 2009 Application in no way contemplates the use of other types of attachment brackets in a washerless assembly, see J.A. 2212−46 (failing to disclose in the [Provisional Application] any other washerless assemblies). The [Provisional Application] never uses the term washerless, or describes any other types of attachment brackets that could be used in the claimed roof mount assemblies. See J.A. 2212−46. D Three’s admission that “[t]here are no statements in the [Provisional Application] . . . that suggest the various attachment brackets cannot be used in a washerless system,” Appellant’s Br.27 (emphasis added), further supports our finding. As we have stated, “[i]t is not sufficient for purposes of the written description requirement of § 112 that the disclosure, when combined with the knowledge in the art, would lead one to speculate as to the modifications that the inventor might have envisioned, but failed to disclose.” Lockwood v. Am. Airlines, Inc., 107 F.3d 1565, 1572 (Fed. Cir. 1997); see Amgen, 872 F.3d at 1374.”

Because the claims in suit were not entitled to priority to the provisional application, the Federal Circuit agreed with the District Court that the claims were invalid over intervening prior art.

This case illustrates the differences between the written description and enablement requirements. It was not questioned that a person having ordinary skill in the art, after reviewing the disclosure of the provisional application, would have been able to make and use the (later) claimed washerless invention without undue experimentation. Rather, this case rests on the question of whether the person having ordinary skill in the art, reviewing only the disclosure of the provisional application, would have understood that the inventor had possession of an invention that included a washerless embodiment without the specific W-pronged attachment bracket. As these facts indicate, this subtle distinction can have significant consequences.

Lessons to be taken from this case include:

- In original filings – and provisional patent applications in particular — include as many variations and combinations of the disclosed embodiments as possible.

- In original filings – and provisional patent applications in particular — include statements that one described aspect can be substituted for another described aspect so as to provide explicit support for as many combinations as possible.

- Ensure later-filed claims are not only supported in the enablement sense, but also have adequate written description in the earliest application to which benefit is claimed.

[1] D Three Enterprises, LLC. v. Sunmodo Corporation and D Three Enterprises v. Rillito River Solar LLC, 2017-1909, 2017-1910 (Fed. Cir., May 21, 2018).